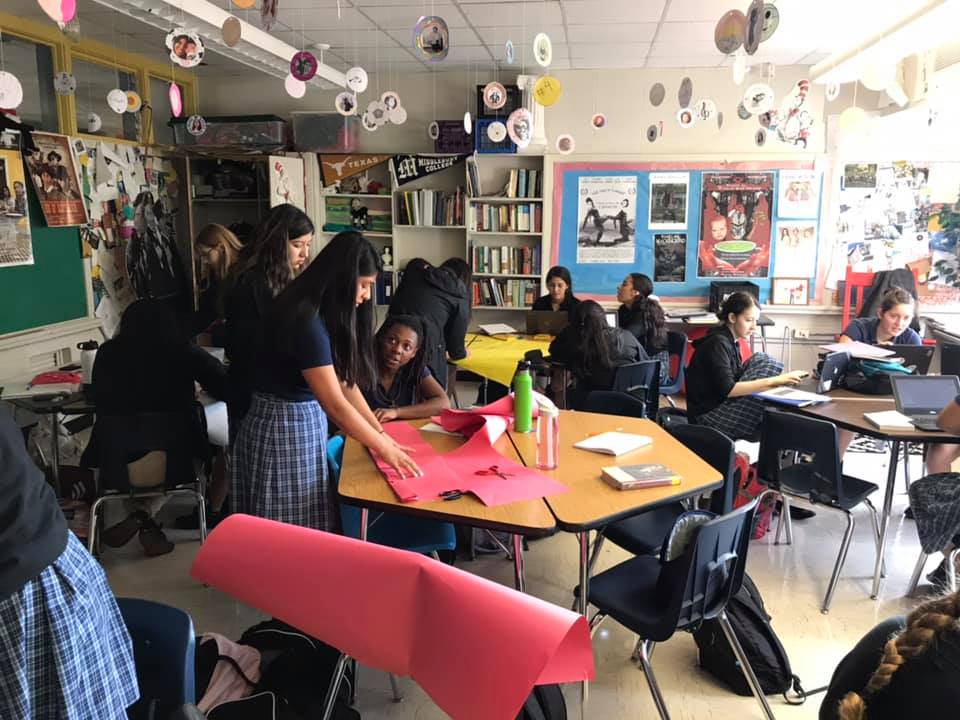

I believe I was 34. I had three children under the age of 3. I had taught 150+ 13-14 year old students each year for the last five years. It was my first time to be on a jury. The defense attorneys should not have let me on the jury. If they were doing their job of defending him, they should not have let several of us on the jury: the older church going Christian grandmother; the trainer for the local University’s swim team (18-22 year old young women). Looking back, I figure his lawyers thought we would be sympathetic to the youth minister because we understood the dreams and desires of adolescent young girls. We understood how they trusted us, and even loved us. We understood the accusations which could be thrown because of childish misunderstandings. Fortunately we did understand, and came to the verdict that the youth minister of the Baptist church near Dallas had broken the promise of in loco parentis, the legal responsibility of a person or organization to take on some of the functions and responsibilities of a parent. That part of that promise that was to not mentally and sexually abuse a thirteen year old girl.

It was a civil trial. Both the former youth minister and the Church were being sued. The statute of limitations for a criminal trial had expired. The young woman was now 21 years old. The prosecutors told us that the evidence for a civil trial was not the same as a criminal trial. It was not beyond a reasonable doubt, but that the preponderance of evidence that lead to a guilty verdict. The preponderance of evidence dropped on us in thick slabs of revulsion for eight hours each of the days the trial lasted. We were asked to determine what percentage of responsibility for the sexual abuse of the young woman lay with the church, or the youth minister.

The trial, they said, would last about 4 days. In the end it went on for two weeks. We heard testimony from the ministers of the church, the deacons, the church women volunteers, the other young members of the church; all those who also went on church trips, attended youth activities organized by the youth ministry, went to pool parties sponsored by the church where the children played games in the pool with the youth minister; who remembered how he and she sat on the edge of the group around the fire at the beach while others sang songs of joy. We heard from the therapist she went to for years after the youth minister’s rape of the young woman. We heard from the young woman. We were given access to her detailed adolescent diary. The same questions were asked of each witness. The answers that were given were so monotonously repetitive that by the end of the second week, I could have answered for each of the witnesses who were called.

We did not hear from the former youth minister. He was a minister of a church in Ohio at this point. He could not be forced to attend a civil trial in Texas. He had moved on from his days as a mere Christian minister to the young souls in his charge in suburban Dallas. God had called him to a new ministry. He was the head of his own church, a respected man. He could not even be impelled to make any monetary restitution that we decided to lay upon him. He was free, forgiven by society, if not by God.

The deliberations in the small room in which we sat were not about whether the events happened; it was beyond debate that the youth minister did what he was accused of doing, but instead circled around how much the church should have known, or did know about the abuse. We were charged with what percentage of guilt lay with each of the defendants, and how much the total monetary fine should be for the actions of the youth minister, who ultimately would not have to pay anything for what he had done to the young woman. What was the price of rape? How much should an institution be held accountable for the actions of an individual member of an organization? Ultimately, we came to a consensus that he was responsible for 80% of the verdict. It was strange sitting in the room, listening to other men arguing for smaller responsibilities to be laid upon the church (because they knew the minister would pay nothing), for a lesser amount of money to be charged to the church, who should have known, who in much of the testimony showed that they did know, about the actions of the youth minister. Too many of the men on the jury seemed to me to be searching for a way to make it all just go away; after all, she let it happen. She let it happen. She was thirteen. He was mid-twenties.

The second decision we were charged to make was the monetary amount that was to be rewarded to the young woman. Here attorneys were asking for 20 million dollars. The foreman of our jury thought that was an absurd amount of money, finally reluctantly acquiescing to 10 million dollars, eight of which the former youth minister would never pay. The other two million being the responsibility of the church.

I remember walking to the bus which would take me to where my car was parked so that I could drive home back to my family with our small children, and then back to my classroom the next day with my wildly wonderful thirteen year old students, thinking that we had all failed her somehow. That justice was bought off cheaply. That we were all responsible for what happened to her. The trial sat in my mind darkly for the rest of the thirty years I worked in education.